Dwellings

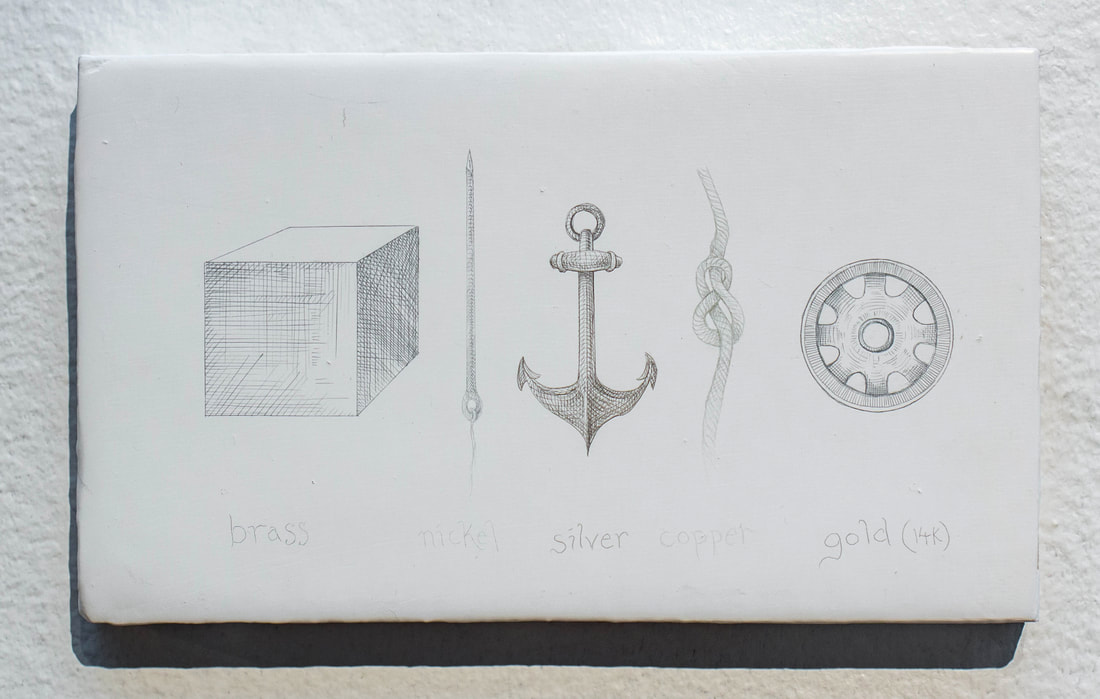

Dwellings is a visual record of the histories and ruins of four civilizations. The images offer the incomplete narratives of the “cliff dwellers,” “forest dwellers,” “sea dwellers,” and “sky dwellers.” These drawings employ silverpoint, copperpoint, brasspoint, nickelpoint, and goldpoint to visually chronicle four different time periods. As the metalpoint oxidizes, these drawings will change mirroring the mutability of time and how we perceive and constantly re-interpret the past, present moment, and potential future of our own civilization.

The drawn records show archaeological sites and remains from ancient, classical, industrial, and nuclear eras. These records show both real and imagined cultural remnants that have been burned, buried, clouded, eclipsed and shrouded. The civilizations investigated are from four unique environments and the correlated drawings function chronologically to demonstrate the increase in trading and shared knowledge evident in the remains of various dwellings. Many of the images show similarities to the cliff palaces of the Ancestral Puebloans, the Sama-Bajau sea gypsies, or the tree houses of the Korowai Tribe; however, the works in the exhibition are alternative histories, allohistory, uchronia, or can be viewed as a version of the multiple histories theory in quantum physics.

The drawn records show archaeological sites and remains from ancient, classical, industrial, and nuclear eras. These records show both real and imagined cultural remnants that have been burned, buried, clouded, eclipsed and shrouded. The civilizations investigated are from four unique environments and the correlated drawings function chronologically to demonstrate the increase in trading and shared knowledge evident in the remains of various dwellings. Many of the images show similarities to the cliff palaces of the Ancestral Puebloans, the Sama-Bajau sea gypsies, or the tree houses of the Korowai Tribe; however, the works in the exhibition are alternative histories, allohistory, uchronia, or can be viewed as a version of the multiple histories theory in quantum physics.

Metalpoint Study, brasspoint, nickelpoint, silverpoint, copperpoint, goldpoint (14k)

Metal Point Technique

Metalpoint is a writing and drawing technique used since the medieval period, but there is some evidence suggesting the techniques were possibly in practice in classical antiquity. After the classical period, lead was the primary metal employed; however, beginning in the late middle ages and into the Renaissance, artists utilized gold, silver, brass, copper, bronze, and tin.

Leonardo da Vinci, Albrecht Dürer, Jan van Eyck, Raphael, Rembrandt, Hans Holbein the Elder and Younger were among those that wielded these materials. Nineteenth and twentieth century artists such as Alphonse Legros, Joseph Stella, and Otto Dix picked up the mantle and helped to continue the metalpoint tradition onto the modern period. As synthesized graphite became more readily available during the nineteenth-century the technique of drawing with metal became increasingly uncommon.

Drawings done in metal are unique in several ways. Aside from gold which is inert, the metal applied to prepared paper or panel oxidizes and thus changes color and tone over time. Depending on how the paper or panel has been prepared, most metals first appear as a faint silvery-gray line similar to graphite. In the case of silver, as the drawn line is exposed to light, air, and other environmental catalysts, it changes into a light sepia, then umber, and after many years the line turns into a rich black. Traditionally, the paper or panel surface for metalpoint in prepared using bone ash or calcium carbonate mixed with a binding agent like rabbit skin glue. Because of how metal point is inscribed into the surface, the mark is indelible and almost impossible to erase.

Leonardo da Vinci, Albrecht Dürer, Jan van Eyck, Raphael, Rembrandt, Hans Holbein the Elder and Younger were among those that wielded these materials. Nineteenth and twentieth century artists such as Alphonse Legros, Joseph Stella, and Otto Dix picked up the mantle and helped to continue the metalpoint tradition onto the modern period. As synthesized graphite became more readily available during the nineteenth-century the technique of drawing with metal became increasingly uncommon.

Drawings done in metal are unique in several ways. Aside from gold which is inert, the metal applied to prepared paper or panel oxidizes and thus changes color and tone over time. Depending on how the paper or panel has been prepared, most metals first appear as a faint silvery-gray line similar to graphite. In the case of silver, as the drawn line is exposed to light, air, and other environmental catalysts, it changes into a light sepia, then umber, and after many years the line turns into a rich black. Traditionally, the paper or panel surface for metalpoint in prepared using bone ash or calcium carbonate mixed with a binding agent like rabbit skin glue. Because of how metal point is inscribed into the surface, the mark is indelible and almost impossible to erase.